Ronald Estrada Seminario

To understand the different gastric pathologies, it is necessary to understand the role played by the defensive barrier and the balance that must exist between it and the offending agents.

It is important to know that the various gastroduodenal pathologies are not always accompanied by hyperchlorhydria, a fundamental fact to apply the correct therapy.

In this chapter we will try to make a brief review about the formation of the gastric defensive barrier and how the different components interact to be more effective protection.

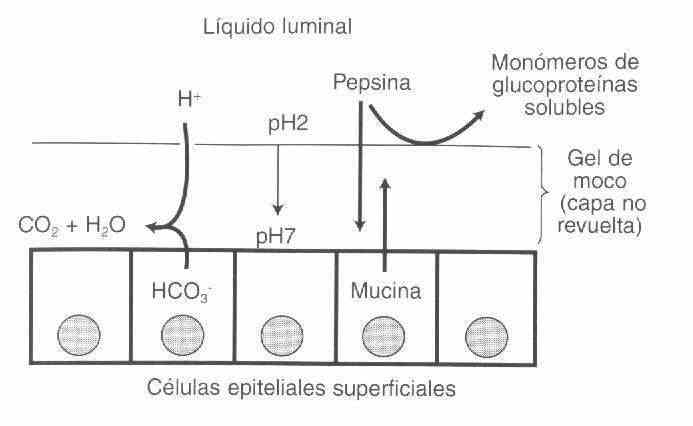

The difference in pH that exists between the surface of the gastric mucus (pH = 1) and that of the surface of the lining epithelium (pH = 7) is necessary to avoid backscattering of ions, which is what causes tissue damage.

Bicarbonate is secreted by surface cells that are rich in carbonic anhydrase; These cells also secrete mucins, so the mucous gel that covers the gastric epithelium has a pH = 7.

Hydrogen back-diffuses very slowly through the gel into the epithelium and meets bicarbonate on its way to the epithelial surface, which transforms it into H2O and CO2. Pepsin follows the same path, which when it encounters pH = 7 becomes inactivated.

The factors that regulate gastric bicarbonate secretion are not entirely clear, but there are two known mechanisms:

Vagal stimulation increases gastric bicarbonate secretion via cholinergic pathways.

Prostaglandin (E2) analogs increase gastric bicarbonate secretion and also act on microcirculation by increasing blood flow.

In addition to bicarbonate, mucus plays an important role in the constitution of the gastric defensive barrier.

Mucous gel exists in two physical forms, a thin layer of mucin that adheres firmly to the gastroduodenal mucosa (sticky mucus) and mucin that mixes with the luminal fluid and can be washed from the mucosal surface (soluble mucus).

This mucin provides surface lubrication and a non-stirred layer of water which slows the diffusion of protons into the mucosa (see figure 1).

The epidermal growth factor, secreted by Brünner's glands, which controls the DNA through the cellular mitotic index, normally allowing the entire gastric epithelium to be replaced within 4 days.

SAME, the biological constituent of the cell, is the most important after ATP, since it activates DNA, forms polyamines, increases sulfhydryls and in particular gastric mucus, that is, glycoproteins. The

SAME is a superior cytoprotective to prostaglandins, a well-proven fact against powerful aggressors such as absolute ethanol and aspirin.

Aggressor agents

Drugs and medications

Aspirin is one of the main aggressors of the gastric mucosa because it blocks the prostaglandins that are responsible for regulating microcirculation and bicarbonate secretion, factors necessary to maintain the pH gradient and thus avoid proton back-diffusion.

Aspirin also by direct action destroys the epithelial cells releasing histamines which increases congestion and subsequent gastric bleeding. The intake of two aspirin tablets causes a loss of 4 to 8 ml of blood, measured by volume and occult blood in fecal matter. All non-steroidal pain relievers cause hidden blood to appear in the stool.

Alcohol in low doses (250ml / day) has a cytoprotective action, but in higher doses it produces direct cell necrosis.

Corticosteroids slow the cellular mitotic rate (cellular aging), degrade gastric mucus and block prostaglandins, facilitating proton back-diffusion.

Bile salts and pancreatic juices

Lecithin plus phospholipase A form isolecithin which at an acid pH is necrotizing of the gastric mucosa; This is what is known as alkaline gastritis.

Gastric irritants

Coffee increases acid secretion and relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter, the same as tea and mate.

Tobacco reduces the tonism of the lower esophageal sphincter favoring gastroesophageal reflux and also produces hypotonia of the pyloric sphincter facilitating pancreatic duodenum reflux (lecithin).

The urea that is eliminated through the gastric mucosa produces congestion and hemorrhage, which only responds to the decrease in uremia through hemodialysis.

Food Allergy

It is quite frequent; chronic erosive and aphthous gastritis respond to this etiology. A separate mention as an entity is eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

Bacteria

Food poisoning, which usually causes gastroenteritis, is accompanied by microbial gastritis. The same occurs with moniliaseic gastritis in which oral thrush is common.

Endotoxinas

They act by causing marked gastric congestion, which, added to any offending agent, produces the hemorrhagic gastritis characteristic of endotoxic shock.

CLASSIFICATION OF GASTRITIS

Gastritis classifications serve two different purposes. The first is to provide a quick overview of the pathology (ie endoscopic and histologic abnormalities and degree of severity). The second objective refers to the associated pathogenesis or clinical associations or both (associated with helicobacter pylori).

According to evolution, they can be acute and chronic.

Acute gastritis is characterized by its congestive appearance and by the transepithelial and transcryptic diapédesis of polynuclear cells.

Chronic gastritis can be superficial with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate of the upper third of the mucosa, chronic atrophic where the infiltrate takes up the entire mucosa and gastric atrophic which is characterized by a decrease in the thickness of the stomach mucosa with total absence of the accompanying fundic glands usually intestinal metaplasia.

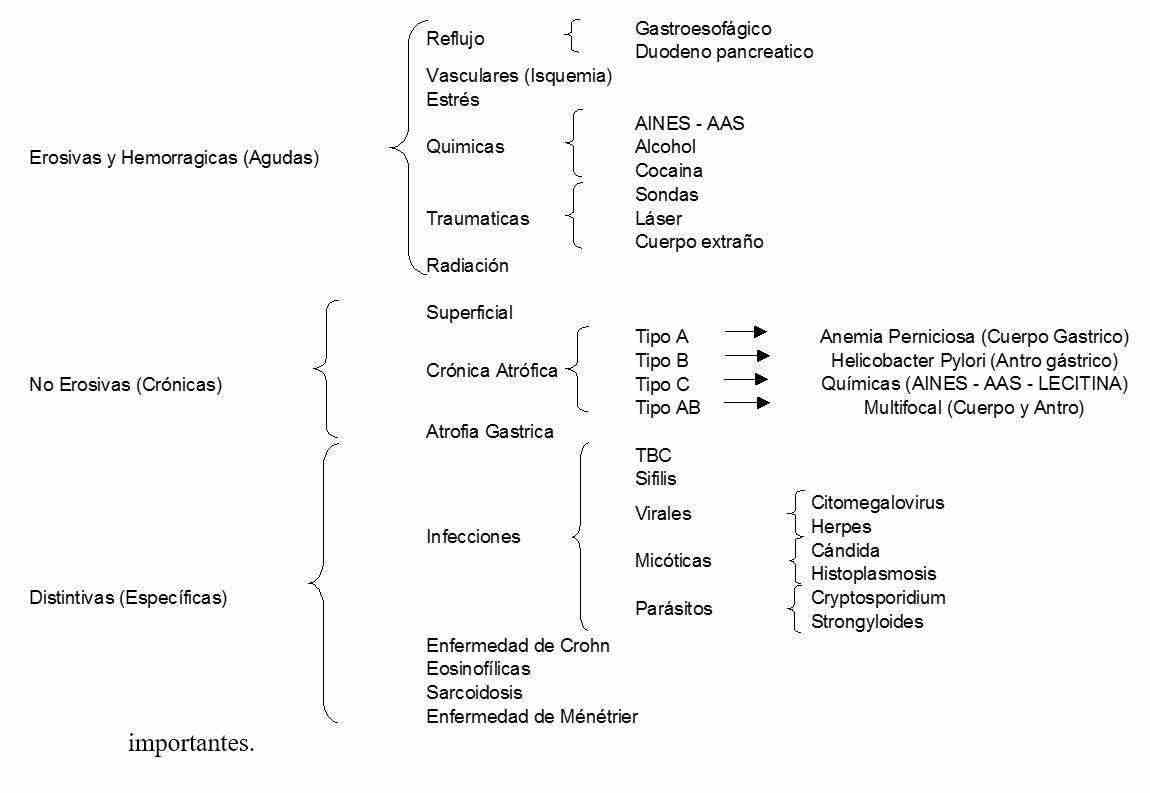

In the attempt to simplify and facilitate the student's understanding, the different classifications will be superimposed and then the most important ones will be developed in detail.

EROSIVE AND HEMORRHAGIC GASTRITIS

Erosive or hemorrhagic lesions are visualized endoscopically and are not usually biopsied, unless a distinctive type of gastritis such as infection or Crohn's disease is suspected.

Erosion is the superficial tear that does not cross the muscularis from the mucosa to the submucosa. Endoscopy reveals generally multiple lesions with white bases and radiated by a halo of erythema, when the erosions have recently bled their base may appear black.

A subepithelial hemorrhage looks like petechiae or striae and bright red patches located on the mucosa or submucosa.

The causes of erosive-hemorrhagic gastritis are alcohol, NSAIDs, nasogastric tubes, ischemia, pancreatic duodenum reflux, gastroesophageal reflux (inflammation of the cardiac region)

NON-EROSIVE GASTRITIS

In non-erosive gastritis, the diagnosis is histological, the endoscopic appearance does not predict its presence, and the histological pattern is nonspecific.

There are three patterns of atrophic gastritis

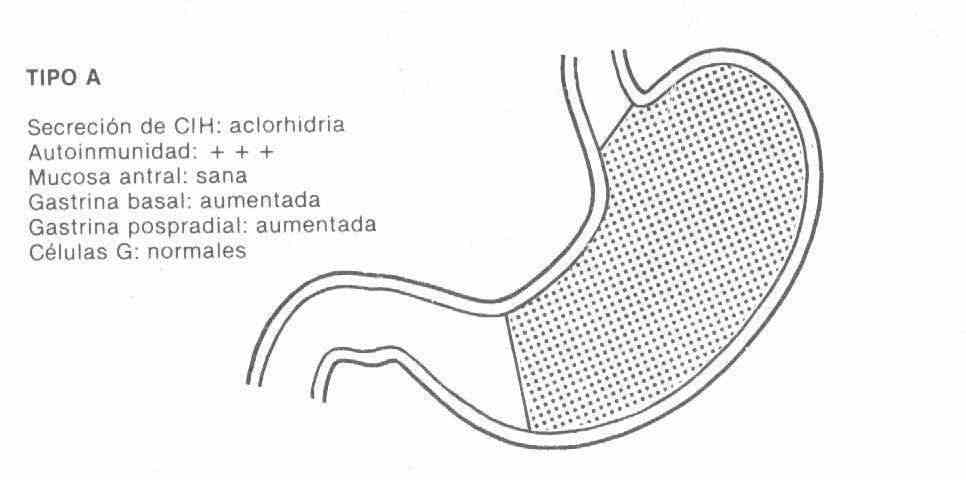

TYPE A : it is associated with pernicious anemia, affected patients have antibodies against the proton pump, pepsinogen and intrinsic factor, the loss of secretory function begins with acid, continues with pepsinogen and finally with intrinsic factor, for what pernicious anemia is a marker for the more severe terminal form of atrophic gastritis type A.

It is located in the gastric fundus, the antrum is healthy. It has high levels of gastrin due to lack of acid inhibition, since it has achlorhydria with zero acid debit.

This type A gastritis is associated with other immune diseases such as hashimoto's thyroiditis, hypothyroidism, diabetes, and vitiligo.

It is rare in our environment and can sometimes progress to malignancy.

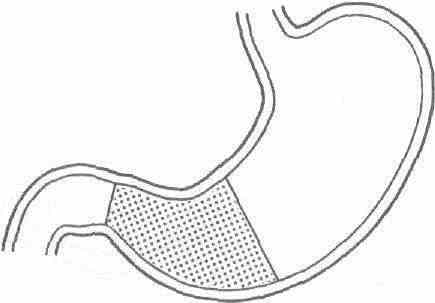

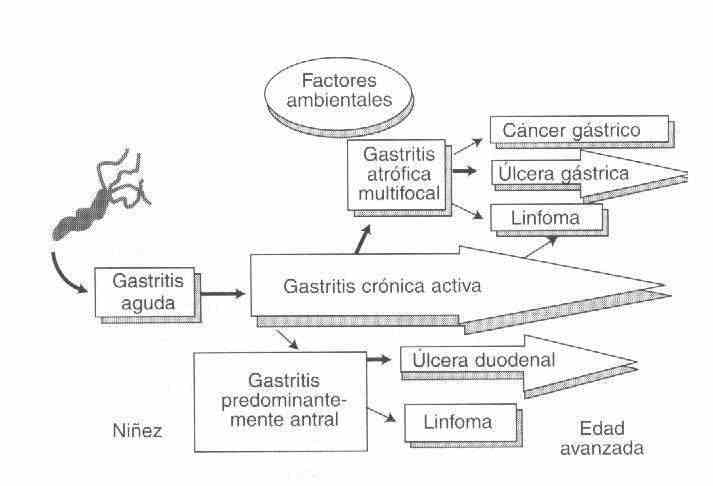

TYPE B : The most important and common cause is Helicobacter Pylori, it begins in the antrum and progressively spreads to the body and the cardia.

Being infectious, it is characterized by a large, predominantly polynuclear inflammatory infiltrate and even presents cryptic microabcesses.

ICH secretion: normal or increased

Autoimmunity: Anticellular G (-) Antibodies

Antral mucosa: diseased

Basal gastrin: normal or increased

Postprandial gastrin: normal or increased

G cells: decreased

Gastrin and acid secretion levels are about 35 to 45% higher in Helicobacter Pylori-infected normal individuals than in non-infected controls.

Due to the importance of the presence of Helicobacter Pylori in this pathology, some considerations will be made in this regard

Helicobacter Pylori is a highly mobile, microaerophilic, slow-growing gram (-) spiral organism whose most notable biochemical characteristic is the production of urease.

Helicobacter Pylori can colonize only gastric-type epithelium, that is, the stomach and areas of gastric metaplasia outside the stomach. The replacement of the columnar cells of the duodenal villi by gastric-type epithelium occurs in 90% of patients with duodenal ulcer, which allows Helicobacter Pylori to colonize the bulb and produce chronic duodenal inflammation.

The route of infection can be oral or oral fecal, gastro-oral (by inadequately disinfected endoscope), by contaminated water or food.

In addition to type B gastritis there are other diseases associated with Helicobacter Pylori such as Gastric Ulcer, Duodenal Ulcer, Gastric Carcinoma.

Non-Hodking Lymphoma - Malt Lymphoma.

TYPE C : is the chemical gastritis caused by the ingestion of ASA, NSAIDs, Alendronate, or the lecithin of bile reflux. It has little or no inflammatory infiltrate.

TYPE AB : it is multifocal with inflammatory islets caused by different strains of Helicobacter Pylori with glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia that are precancerous lesions.

It begins in the region of the angular incisura then spreads proximally and distally.

Distinctive gastritis

Tuberculosis : its frequency has increased due to the association with AIDS.

There is pyloroduodenal involvement, with multiple ulcers, thickening of the gastric wall, and obstruction of the pyloric outflow tract.

The specific diagnosis is based on the demonstration of caseous granulomas in biopsy tissues and in positive cultures.

Syphilis : like TB, its frequency increases due to the association with AIDS

The picture is similar to that of gastric linitis or lymphoma and therefore presents with nausea, vomiting or early satiety.

Cytomegalovirus : seen in immunocompromised patients (AIDS- Liver and kidney transplants, etc.)

In the stomach the most striking aspect is the thickened gastric folds in the antrum or a localized or diffuse process in the gastric body.

Cytomegalovirus affects deeper layers of the mucosa, in endothelial cells and mucous glands, unlike Herpes Virus, which lesions are superficial.

Ménétrier gastritis: Ménétrier gastritis is a rare entity, characterized by protein-rich hypersecretion and hypoalbuminemia, accompanied or not by edema, ascites and even anasarca. The patient has no signs of kidney, liver, or heart disease, he normally ingests protein, and the etiological cause of his loss of albumin is not found. The double-contrast gastroduodenal serial radiograph shows giant folds, the study of gastric secretion reveals hypochlorhydria, and the gastric biopsy shows a chronic gastritis with a tendency to atrophy.

The diagnosis will be made using albumin marked with I, its half-life will be noticeably shortened, less than eight days. Radioactivity in fecal matter will show a striking increase. In gastric juice, radioactivity can be measured and an electrophoresis proteinogram performed, in which a typical albumin band will be observed.

Hypersecretory hypertrophic gastritis : This is a patient generally with a history of chronic intractable gastroduodenal ulcer or a gastrectomized with recurrent ulcers, or a patient with chronic diarrhea with steatorrhea. He presents a marked baseline gastric hypersecretion whose output is similar to or represents more than 60% of the maximum post-stimulus output. In these circumstances, a Zollinger-Ellison syndrome should be considered, produced by a gastrinoma located in the pancreas or duodenum; This tumor secretes high concentrations of gastrin and causes marked basal gastric hypersecretion and intractable ulcer or chronic diarrhea. Faced with this presumptive diagnosis, a gastrin dose should be performed by radioimmunoassay and eventually a secretin test.

Hypersecretory glandular gastropathy : In this rare entity there is a marked hypertrophy and glandular hyperplasia of unknown etiology, which presents with marked hyperchlorhydria; the patient is usually a carrier of an intractable duodenal ulcer and surgery means cure of the disease. Gastrinemia is normal.

Symptoms

The symptomatology is polymorphic, variable with food, bilious, mucous and sometimes hemorrhagic vomiting, which may or may not be preceded by nausea. Epigastric pain has no hourly, daily or annual rhythm, the patient feels better on an empty stomach.

In acute gastritis, when the triggering causes are suppressed, the symptoms remit in a few days.

There are forms of presentation that may be indicative of gastritis

Hemorrhage

Achlorhydria or Pernicious Anemia

Ascites, edema, giant gastric folds, hypoproteinemia with hypoalbuminemia (Ménétrier's disease)

In summary, attempts to establish a correlation between gastritis and a specific symptom picture have failed.

Study methodology

The diagnosis of gastritis is the heritage of the biopsy and its histopathology, except in hemorrhage where it is established by endoscopy.

The gastroduodenal serial radiography with double contrast may show

chronic erosions, in the form of small rounded lacunar images, which will be confirmed by fibroscopy; other times there will be giant thick folds, which will pose the differential diagnosis between a Ménétrier-type protein-losing gastritis, a gastric lymphosarcoma, or a Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. In chronic type A gastritis of pernicious anemia, the radiologist V. D'Allotto described the following signs: tubular stomach, bald gastric roof and smoothness of the greater gastric curvature, which are not pathognomonic, since thick or thin gastric folds they depend on the contraction of the muscularis mucosae.

The Kay test measures maximum gastric secretion using histamine, with which 100% of the parietal cells are stimulated. This test is the most reproducible and reliable. The normal debit is 10 to 25 mEq / hour; in gastritis, the debit is generally normal, and has a value when it is zero or close to zero. The latter is valid for plasma pepsinogen or uropepsinogen, whose levels have value when they are close to zero and indicate gastric atrophy or pernicious anemia.