Oscar M. Laudanno, Oscar A. Bedini

The set of abdominal signs and symptoms, including spontaneous and / or provoked pain, vomiting, constipation, muscle contracture and / or defense, abdominal distension, accompanied by general manifestations (such as fever, tachycardia, anemia of sudden installation) that can appear in a patient gradually or suddenly, and whose evolution can be progressive and lead to hospitalization and / or early surgical treatment, and in other cases to adequate medical treatment, such as hepatic colic kidney, constitutes what has been called "acute abdomen"

Consultation for abdominal pain is a frequent reason in medical practice; the causes that cause it include diseases with little or no risk to the patient's life, or they can be serious abdominal problems.

The correct pathophysiological and etiological diagnosis is the foundation of effective therapy.

In acute abdomen, diagnostic accuracy must be followed by the conduct to be followed. it is necessary to interpret the signs and symptoms and anticipate the progression of the morbid process.

The diagnosis must go through a stage of orientation in the home of the patient, and of closer approximation in the hospital, stopping this must proceed to the interrogation about: past operations (flanges and adhesions) old ulcer dyspepsia (perforated ulcer), preexistence of pain with fighting peristalsis and old hernias (mechanical ileus), last period (ectopic pregnancy), soft epigastric beginning irradiated to the right iliac fossa (appendicitis) etc. The best elements for the diagnosis will be obtained many times, taking into account the previous clinical history (operations, ulcers, lithiasis, heart disease, diabetes, etc.) the possible precipitating factors (binge in pancreatitis and cholecystitis, efforts in the aortic aneurysm broken, etc.) the type of pain, the presence of vomiting, diarrhea or constipation

It is worth taking into account some data that can help to make the diagnosis of acute abdomen. Age allows us to consider those processes with a tendency to occur in certain groups of patients, for example: the most frequent intussusception in infants or appendicitis in young people. With regard to pain, it must be taken into account that it can be overlapping (appendicitis) violent (perforated gastroduodenal ulcer); its relationship to breathing (peritonitis and abscesses hurt with breathing). Alterations in diuresis: frequency, by irritation of the detrusor. Menstrual history: cycle characteristics, last menstruation, nature of menstrual flow.

Experience has made it possible to determine the most frequent causes of acute abdomen and to correlate them in 3 major syndromes: peritonitis, hemorrhage or mechanical occlusion, without neglecting mixed causes, such as vascular, tension and retroperitoneal.

The doctor must collect a complete and detailed medical history, and question the patient's relatives, thus summarizing more information. " there is no greater wisdom than knowing the beginning or origin of things ”(Bacon). Second, a complete physical examination should be performed, where inspection, palpation, percussion, and abdominal auscultation are the semiological steps by which fine pathological expressions can be captured. It is extremely necessary to dedicate the necessary time to the physical examination as this will contribute to a better clinical and surgical judgment.

If the condition is very acute, it is necessary to formulate diagnostic hypotheses, and hospitalize the patient urgently. Laboratory tests and corresponding complementary studies will be requested without ever omitting a chest film from the front and profile, and a standing and lying abdominal film.

Abdominal pain

Pathophysiology of pain. Abdominal pain is a consequence of the intervention of four elements: the exciting stimulus, a receptor structure by peripheral fibers, a nerve pathway that carries the stimuli, and the nerve centers of sensation and pain

to. Triggering stimuli. They can be grouped as shown in Table 31-1

b. Peripheral receivers. Although under normal conditions and for low intensity stimuli, the viscera can be considered as insensitive, they are not so under pathological conditions and for stimuli. intense, such that acute abdominal pain is really visceral pain caused by stimuli not only from the peritoneum, but also from other components of hollow viscera. Pain receptors are located in the wall of the viscera. hollow, in the capsule of the solid ones, in the wall of the vessels, in the peritoneum and in the mesentery.

c. Pathways and centers of pain perception.Painful sensations are mediated by afferent pathways consisting of three neurons: the first is located in the posterior root ganglion, the second is in the optic thalamus, and the third in the cerebral cortex.

The splanchnic nerves carry the stimuli received in the posterior parietal peritoneum, pelvic, anterior parietal peritoneum and mesentery, which reach the medulla via the spinal or intercostal nerves. The stimuli received. in the diaphragmatic zone they are carried by the phrenic nerves. Reflex arcs can form when some fibers connect with efferent motor neurons; Sometimes, for this reason, severe abdominal pain can lead to changes in heart rate or variations in blood pressure, or intestinal motility can be interrupted, causing a reflex ileus, as occurs in certain vertebral trauma. or in retroperitoneal hematomas

The stimulation of the motor neuron by fibers from the parietal peritoneum causes muscle contracture: The fibers of the painful sensation cross on the opposite side of the spinal cord, forming the lateral spinothalamic tract, then connecting with the second neuron of this pathway, which is located , as mentioned above in the optic thalamus; from there other fibers reach the cerebral cortex, where the third neuron of the sensory pathway is located.

In the thalamus the unpleasant component of the painful stimulus is probably perceived, while the cerebral cortex localizes the pain at the point of its stimulation. The afferent pathways of the autonomic nervous system consist of two neurons. According to the neurotransmitter that is released in the nerve endings of the second neuron, it is divided physiologically into the nervous, autonomic, sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The sympathetic releases adrenaline or noradrenaline in its intersynaptic spaces, while the endings. parasympathetic discharge acetylcholine. Lately, a third system, called the peptidergic system, has been shown to play a very important role in the digestive system,

|

Table 31-1. Triggering stimuli for abdominal pain

|

Clinically, and through knowledge of these nerve pathways, three types of abdominal pain can be observed: visceral, somatic and referred pain.

| Table 31-2. Divisions of the gastrointestinal tract, according to embryological development. | |||

| Sector | Components | Arterial irrigation | Related to |

| Small bowel |

|

Celiac trunk | Epigastric pain |

| Middle intestine |

|

Superior mesenteric artery | Periumbilical pain |

| Posterior intestine |

|

Inferior mesenteric artery | Epigastric pain |

Types of abdominal pain

Visceral pain : It is produced by the following mechanisms:

- Due to distention of the capsule of the organ: Ex. Hepatitis liver pain, pain from heart failure and biliary obstruction.

-

Due to increased pressure within a hollow viscus: For example, due to distention, or muscular contracture, (intestinal, urethral, hepatic colic, contracture of the fallopian tubes).

It is intermittent and generally subsides with the administration of antispasmodics. - Due to acute ischemia: mesenteric vascular infarction.

- By inflammatory processes.

Visceral pain is characterized by being poorly localized, generally diffuse and deeply perceived. From an embryological point of view, the gastrointestinal tract is divided into three sectors, the characteristics of which are described in Table 31-2.

Numerous metabolic diseases can cause abdominal pain. Among them are:

- Hyperparathyroidism and hyperlipidaemia (acute pancreatitis).

- Porphyria and saturnine colic (hyperperistalsis).

- The Addisonian crises (hydroelectrolyte imbalances).

- Diabetic acidosis and uremia.

Somatic pain. Stimulation of the parietal peritoneum, the diaphragmatic peritoneum, and the root of the mesentery cause somatic pain. It is generally sharp and well localized by the patient. Topographically it corresponds to the place where the stimulus originates, and is accompanied by muscle contracture; This is because the afferent fibers reach the same side of the spinal cord, while those responsible for visceral pain intersect on both sides of the cord (lateral spinothalamic bundles). Somatic and visceral pain occurs in acute appendicitis; the inflammation of the wall of the appendix is perceived in the epigastrium or sometimes diffusely in the abdomen (visceral pain), whereas when increasing: the inflammatory process and making contact with the parietal peritoneum, the pain becomes more localized,

Referred pain . It is perceived at a distance from the diseased organ; eg, shoulder pain in perihepatic inflammatory processes and subphrenic abscesses; pain in the lumbar region in cases of uterine or rectocolonic pathology; testicular pain in renal colic. When an intense stimulus reaches the spinal cord, through the peripheral nerve pathways, and discharges its impulses in the same place as somatic afferent fibers, the cerebral cortex perceives said stimulus and makes the pain perceived in the location of the corresponding area to the dermatome of the spinal cord; p. Eg, the fibers of the reproductive organs reach the inferior mesenteric ganglion, connecting with the segments Ll, L2, and L3 of the spinal cord. Fibers from cutaneous areas correspond to dermatomes S3, S4, S5.

Stimulation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic system by the presence of strong somatic and visceral pain can trigger a series of symptoms, namely: sweating, nausea and vomiting, tachycardia or bradycardia, skin hyperesthesia, etc.

Classification of the causes of acute abdomen, according to the mode of onset of pain.

They are listed in Table 31-3.

|

Table 31-3 Causes of acute abdomen, is the mode of onset of pain

|

Pain peculiarities

Location and radiation of pain . Stomach and duodenum: epigastric pain with radiation to the back.

Small intestine and right half of the transverse : periumbilical region. and sometimes lumbar irradiation.

Descending colon, rectum, sigmoid and transverse colon in its left half: hypogastric pain with lumbar irradiation.

Tubes and ovaries : right and left of the suprapubic area.

Acute appendicitis : onset, with epigastric or periumbilical pain. and then in the right iliac fossa; from the beginning in the latter.

Bile ducts and gallbladder : right upper quadrant radiating to the back and right shoulder.

Diaphragmatic processes : pain in the hypochondria radiating to the lateral furnace shoulder and scapular region.

Renal colic : starting in the lumbar region, then following the direction of the ureter to the ipsilateral testis.

Pancreatitis : epigastric pain radiating to both hypochondria and the back; in the presence of exudate there may be pain in the iliac fossae.

Character of pain

In colicky pain , which occurs with intermittent exacerbations, as in the case of hollow viscera obstruction; this intermittence is less in the case of high obstructions; when strangulation is associated, the pain becomes continuous. Colicky pain does not disappear completely in lithiasic or ureteral obstructions.

Abdominal pain can be profoundly severe , in pancreatic or biliary pathology. In the event of a dull pain , congestion of a solid viscus or retroperitoneal affections can be considered. (pancreatic disease).

Sharp, stabbing pain is characteristic. of peritoneal inflammation (exudate from perforated ulcer).

Intensity . They present severe abdominal pain: 1) vascular disorders: embolism and mesenteric thrombosis; 2) acute pancreatitis; 3) renal colic; 4) d lead poisoning; 5) perforated ulcer and 6) ruptured aneurysm.

Association with vomiting . It is very common for abdominal pain to be associated with vomiting, especially in processes of the biliary and pancreatic tract, and largely in upper intestinal obstruction. When the obstruction is low (colon), vomiting is generally scarce. Faced with a condition with non-bilious vomiting, it should be assumed that the cause of the obstruction lies above the mouth of the common bile duct. Vomiting is usually immediate in case of an upper intestinal obstruction, or in colic. liver When they occur several hours after the onset of abdominal pain, one should think about a lower intestinal obstruction or appendicular processes.

Position of the patient before abdominal pain. All those processes that irritate the pelvic peritoneum provoke. contracture of the iliopsoas muscle and the patient will appear flexing the muscle on that side, in order to relieve pain; a typical example is retrocecal appendicitis. The patient remains immobile in acute generalized peritonitis, since the slightest movement causes pain. In pancreatitis he adopts a position of Mohammedan prayer, with dorsiflexion. On the contrary, the patients. with renal colic they move intensely from one side of the bed to the other, anxious and restless.

Vomiting Vomiting recognizes different mechanisms:

- Sudden irritation of the parietal, mesenteric or diaphragmatic peritoneum (eg, acute pancreatitis due to irritation of the solar plexus).

- Increased pressure within the ducts (eg, hepatic and renal colic, cholecystitis, distended intestine in occlusion).

- Irritation of the gastric mucosa (eg, ingestion of medications, or spoiled food).

- Intracranial hypertension.

- Electrolyte disorders: acidosis. and hyperkalemia (eg, diabetic acidosis, Addisonian seizures, uremia).

- State of shock: due to reduced O2 supply.

Muscle contracture. It is thus defined as the intense spasm of the striated muscle fibers. Any inflammatory process of medium intensity, or any aggressive stimulus on the parietal peritoneum, causes contracture of the ipsilateral muscles:

- Presence of secretions in the peritoneal cavity: ulcer perforation, suture dehiscence, perforated diverticula in the colon or small intestine.

- Inflammatory processes: acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, acute pancreatitis.

- Presence of blood: ectopic pregnancy, fissured aortic aneurysms, fissured liver tumors, spleen rupture.

- Viscera distention: cecum distention in cases of sigmoid obstruction with a continent cecal valve, with irritation of the parietal peritoneum.

Muscle contracture is relatively easy to detect when the process that stimulates the parietal peritoneum corresponds to the anterior wall of the abdomen; On the other hand, it is made more difficult when the inflammatory process is located in the pelvis or in contact with the diaphragm, or with the posterior parietal peritoneum. In the first case, the obturator muscle or iliopsoas contracture is sought, causing pain through the rectal or vaginal examination Involvement of the subdiaphragmatic peritoneum paralyzes the diaphragm, so that it is the intercostal muscles that perform the respiratory function. The irritation of the posterior parietal peritoneum determines a less intense muscular contracture, due to the smaller quantity of receptor fibers of stimuli; moreover, the efferent fibers are less numerous.

Bowel transit disorders

Gases and liquids normally travel through the gastrointestinal tract to the rectum. The interruption of this physiological fact originates a set of symptoms and signs that constitute the intestinal obstruction syndrome.

It is characterized by abdominal pain, vomiting, meteorism, lack of emission of gases and fecal matter, associated with disorders of water and electrolyte metabolism, and acid-base balance. This picture constitutes a medical-surgical emergency.

Mechanical occlusion. This is the name given to the complete difficulty. or incomplete in intestinal transit, caused by a physical obstacle (bridles, tumors).

When intestinal peristalsis is ineffective, weak and insufficient, a paralytic or adynamic ileus is installed; if instead the contraction is exaggerated it is called spasmodic ileus (eg, porphyrias and plumbic intoxication).

The obstruction can be located in both the small and large intestines, and can be total or partial.

In any occlusive condition, the compromise of the irrigation of the affected sector can be added to the mechanical cause; in cases of intestinal strangulation, there is overlap, obstruction plus necrosis. If the vascular compromise is primary, it is a vascular ileus. An example of a strangulated obstruction is a strangulated hernia. An example of vascular ileus is mesenteric embolism. The causes of mechanical bowel obstruction are listed in Table 31-4.

Mechanical ileus with strangulation. It occurs due to the following causes: a) volvulus, b) intussusception, c) flanges, d) strangulated external hernia, e) internal hernia, f} infarction, and g) closed occlusion of the colon (with continent ileocecal valve).

Paralytic ileus. It is observed in the following cases: a) surgical interventions b) peritonitis, c) untreated mechanical obstruction, d) sepsis, e) fluid and electrolyte disorders, f) retro-peritoneal hemorrhages, g) pelvic and spinal fractures, and h) anticholinergic drugs.

Spasmodic ileus. It is caused by: a) postoperative, b) reflex, and c) spontaneous.

Peritonitis, inflammatory processes (appendicitis, cholecystitis) and intense painful stimuli, reflexively provoke stimulation of the sympathetic system, which determines the decrease or absence of intestinal peristalsis, which can lead to a clinically objective regional or generalized ileus by auscultation and radiographic studies.

Diarrhea is a common symptom in gastroenteritis. When it is bloody it can correspond to colonic ischemia. Pelvic appendicitis and abscesses. they can lead to straining and tenesmus due to contact of the inflammatory process with the rectum.

|

Table 31-4 Causes of mechanical intestinal obstruction

|

Tachycardia

This sign may vary according to the processes that involve the abdomen, and may be related to:

1) volume changes: generalized peritonitis. with the formation of a third space, intestinal obstructions, gastrointestinal bleeding within the lumen or in the abdominal cavity; 2) stimulation of the sympathetic (by catecholamine release), and 3) elevation of the. body temperature.

Tachypnea

The control of the respiratory rate is another parameter to take into account. It is modified in any serious disease and can vary by:

1) involvement of the diaphragmatic peritoneum with paresis of the diaphragm muscle and breathing by the intercostals; 2) chronic diseases, 3) septic states, and 4) acute infectious diseases due to increased body temperature.

Fever

The increase in body temperature responds to the presence of an inflammatory, abdominal or extra-abdominal process, except in patients with high malnutrition or in a state of cachexia, immunosuppressed, elderly, carriers of chronic diseases, etc. In the abdomen some characteristic pictures can be mentioned such as: acute suppurative cholangitis, where fever, chills, hypotension, jaundice, neurological disorders, indicate the presence of pus within the bile duct. High temperature is also observed in case of necrosis of the viscera due to mesenteric thrombosis, or in perforations of the viscera: hollow. Abdominal abscesses are manifested by fever, needle type;

Symptoms and signs

It is extremely important to collect the data from the medical history, doing it carefully, allowing the patient to express himself well, without interfering or directing the questioning. With some frequency, the family members are in charge of recounting the characteristics of the condition that occurs due to the patient's psychophysical impossibility.

The history of habitual drug ingestion is important , either for short or long-term treatment, as occurs in rheumatic diseases with the consumption of aspirin or anti-inflammatory drugs.

Pain relief with prior antispasmodic administration suggests colic pathogenesis. Drinking large amounts of alcohol is of great value in acute pancreatic syndrome. Cholecystitis, biliary colic, acute pancreatitis may occur after an abundant intake of high calorie content.

The myocardial infarctions posterior wall manifested by an ECG signs of ischemia and injury, and toracoepigastralgia with dizziness and collapse; there may be stasis hepatalgia with engorged jugulars. The aortic dissecting aneurysm medionecrosis and exhibit epigastric radiated into legs and arms and hypertension with normal ECG and femoral pulses nonpalpable.

The embolism or thrombosis of the mesenteric arteries is accompanied by hipogastralgia, abdominal defense, signs of peritonitis and emission of red feces.

The periarteritis nodosa shows epigastric pain, prolonged fever, uremia, polyneuritis and leukocytosis.

The abdominal purple manifests. in less with reddish stools, arthralgia and nephritis; and morbilliform cutaneous purpura.

The diabetic acidosis is accompanied by vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, epigastric pain, asthenia, dehydration, polyuria and hyperglycemia.

The Addisonian crisis presents melanoderma, hypotension, adynamia, hypothermia, and abdominal pain.

The acute porphyria is characterized by vomiting, ileus paralytic aspect mesogastralgia, polyneuritis, leukocytosis and porphyrinuria.

The perforations are manifested by knifelike, belly table, cold sweat and collapse,

The acute pancreatic necrosis appears after heavy meals: and evidenced by epigastric pain with irradiation left, vomiting, glucosuria and late periumbilical blue spots.

The ileus, strictures and intestinal occlusions show retention of gas and stool after a fighting peristalsis, with cramping pain and vomiting, and finally fecaloid vomiting. Paralytic ileus is often postperitonitic; It is appropriate to look for hernias and perform a rectal examination; radiology shows air-fluid levels and inflated loops.

The nervous and digestive colic spasms reveal neurovegetativa dystonia and there are nervous and hysterical stigmata, with sharp and bulky muscle pain without defense, expulsion of feces and gases, vomiting, removal of mucus in the stool

The colic lead manifest. due to anemia, Burton's border, radial paresis, erythrocytes with basophilic stippling, porphyrinuria and constipation.

The tabes present radiculitic crisis; pupils, rigid, lack of reflexes, VDRL and positive Wassermann reaction.

The perforativa cholecystitis is characterized by subictericia, right upper quadrant pain and localized defense, and vomiting.

The appendicitis exhibits initial epigastric pain, then pain in the right iliac fossa point of Mac Burney and DRE positive, leukocytosis, and cutaneous hyperesthesia defense.

The renal colic is lumboabdominogenital pain, vomiting, dysuria, micro and macroscopic hematuria and pain in the percutir in the kidney area.

The acute adnexitis relates to the period or abortion or delivery. Present. fever, discharge, high erythrocyte sedimentation, tension in the iliac fossae, painful vaginal examination, peritoneal reaction and lumbar pain.

The follicular rupture manifested by intermenstrual pain, no fever, normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and mild abdominal pain and sacral defense.

The torque of an ovarian cyst produces defense, lower abdominal pain with palpable tumor, bladder reflects retention and sometimes fever.

The inguinal hernia nestled presents. local signs, reflex epigastric pain and sometimes ileus.

Physical exam

Inspection

Observation of the conjunctivae may indicate the presence of jaundice, paleness, and anemia. A dry tongue with increased folds is a sign of dehydration, as is dry skin. This may show stretch marks due to elastic fiber breakdown. by processes that distend it, such as pregnancy, tumors, ascites, etc. There may be paleness in the ruptured spleen, with massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage. The presence of ecchymotic spots around the umbilicus, or in the iliac fossae, is a sign that reveals a retroperitoneal hemorrhage; it is seen in ectopic pregnancy and in acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis. In Schönlein-Henoch syndrome, purpuric lesions are seen.

The patient should be made to cough in order to determine if abdominal pain intensifies or if tumors appear at the level of the hernial orifices;

A distended and symmetrical abdomen may be due to the presence of air or fluid in the cavity. peritoneal (eg, long-standing perforated ulcer), colonic obstruction or paralytic ileus, ascites, or pregnancy.

When the distention is chronic as in ascites, the umbilicus is everted; when it is rapid, it does not, except that it coexists with an umbilical hernia. Asymmetric distention is seen in volvulus obstructions, or in pancreatic pseudocysts or ovarian cysts.

In women, breathing is predominantly costal and the abdomen does not move or moves very little; in man, on the other hand, the abdomen excursions with the breath; decreased movement is a sign of diaphragmatic paralysis, or of peritoneal inflammation or contracture of the abdominal muscles. In addition, peristaltic waves from an intestinal loop, fighting an obstruction, can be revealed; These waves are called the Kussmaul type and are directed towards the right iliac fossa. In the infant, Bouveret waves, which are the fighting expression of the stomach, can be found in congenital hypertrophy. of the pylorus, and in this case they are limited to the epigastrium.

Dilated loops are usually evident under the abdominal wall in a thin patient, constituting the sign of the ladder. The mass tonic contraction of the stomach is observed in the epigastrium, more to the left than to the right, and constitutes a sign called intermittent Cruveilhier hardening; the same phenomenon, when it is of the intestine, resides in any part of the abdomen, in relation to the topographic projection of the enteric segment that determines it, and it is the rigid intestinal distention, or "rigor" of the Italian authors, which means short stiffness duration.

The temperature recording is extremely important in the case of septicemia, shock, acute pancreatitis, intestinal obstruction or perforation of a gastroduodenal ulcer; the temperature is usually normal; high fever is rare in early abdominal disease and is found in acute peritonitis. The most important thing is to look for the temperature in the armpit and rectum and to investigate, if there is axillorectal dissociation; under normal conditions the difference is up to 1.5 ºC, being higher in the rectum. In acute abdominal processes the difference is greater.

Palpation

Before starting. Upon palpation, the examiner should ask the patient to cough. In the presence of peritoneal irritation, the cough will cause pain, sharp and stabbing, over the affected region; this allows the examination to be carried out leaving the area of maximum sensitivity for. Last term. The patient should be in the supine position, with the arms resting along the body and the legs flexed in slight abduction.

Superficial palpation . It is the initial procedure to discover slight degrees of sensitivity or muscular defense. produced by underlying viscera disease. It consists of gentle superficial palpation with the hand, which should be at a comfortable temperature for the patient.

The main findings are:

-

Defense: it is an increase in tension of the abdominal wall. It will be evaluated by palpating both sides of the abdomen simultaneously, with both hands; defense over an inflamed organ (cholecystitis, appendicitis) is considered as evidence of peritoneal irritation, or peritonism. It is more voluntary than reflexive, and may disappear if the patient is anesthetized or distracted. It may be accompanied by pain on decompression (Guéneau de Mussy's sign). Both are generally the first, signs of peritonism.

When finding stiffness of the abdominal wall without decompression pain, it can be thought that the picture has an extra-abdominal origin: myocardial infarction, dissecting aneurysm, pneumonia, pleurisy, pericarditis, etc. - Contracture: it is a greater degree of resistance of the abdominal wall. It differs from the defense in that it is reflexive and involuntary, and it does not allow a deep palpation. It can be generalized ("table belly") or localized, and semiologically indicates peritoneal inflammation or peritonitis. Inflammation of the pelvic peritoneum does not cause abdominal wall contracture.

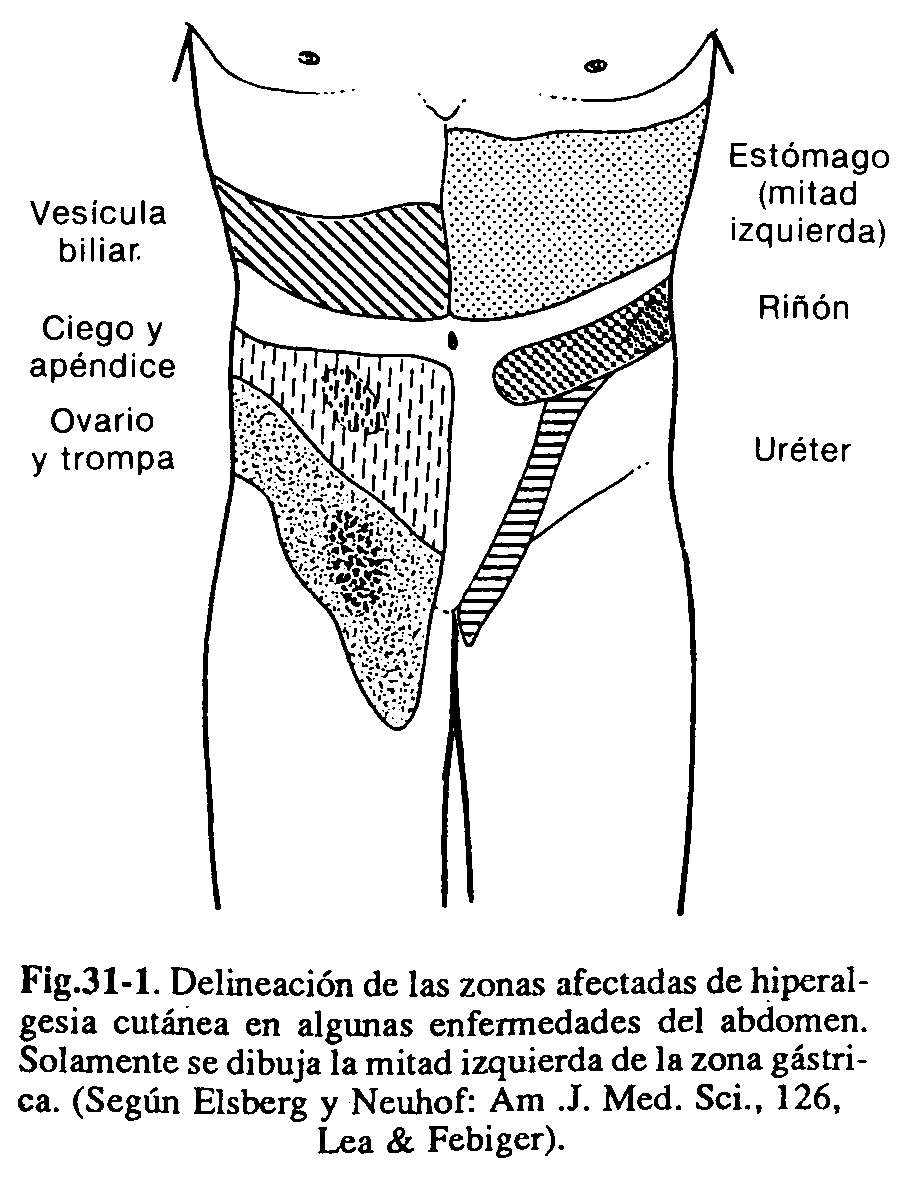

- Cutaneous hyperesthesia: can be determined: the hypersensitivity of the skin by contact with the tip of a pin or a piece of cotton, or by causing a light rubbing with the nail. Areas of greatest proprioceptive sensitivity may indicate a peritoneal inflammatory process (Fig. 31-1).

- Hernial orifices: they should be examined carefully, since it is very common to find cases of acute abdomen that are recognized as the cause of strangulation of a hernia.

- Diseases of the abdominal wall: the presence of a painful mass in the hypogastrium, to the right or left of the midline, accompanied by pain, sometimes of great intensity, requires the exclusion of a rectus sheath hematoma. The triggering cause may be: pregnancy, abdominal trauma, severe cough and treatment with anticoagulants; When the rectum contracts when sitting down and the mass is still palpable, it indicates that the mass is extra-abdominal since otherwise it would be difficult to palpate.

Deep palpation . It allows determining the size and shape of the intra-abdominal organs (liver, spleen, kidney, etc.) as well as discovering. any abnormal formation in said cavity.

Specific signs . Sign of rebound or decompression pain. Search for decompression pain should not be attempted until the end of the abdominal examination, because it can cause great discomfort and the patient will not achieve relaxation, making further examination difficult. of the abdomen.

This sign is obtained by applying deep pressure to the abdomen, at the level of a region away from the suspected inflammatory process and then performing a rapid decompression. When there is localized peritoneal irritation at the level of the inflammatory process, there will be pain in that region, while if the irritation is diffuse the pain will awaken at the compressed site level. When it occurs throughout the abdomen, it is called the Guéneau sign of Mussy; in the right iliac fossa, Blumberg's sign (appendicitis).

Psoas sign . On many occasions, the intra-abdominal inflammatory process (inflamed serosa) determines inflammation and contracture of the muscle that is underneath; To be able to find it, the patient is asked to flex his thigh against the resistance imposed by the same examiner with his hand. Said, movement determines the contracture of the muscle, causing intense pain if an inflammatory state exists.

Internal shutter sign . Similar to the previous one, it is obtained by flexing the thigh at 90ºC and making an internal and external rotation with it; it will be positive if abdominal pain appears, and indicates irritation or inflammation of the pelvic peritoneum. In these circumstances, gynecological examination and digital rectal examination are important.

Murphy's sign . It indicates inflammation of the gallbladder, and consists of exerting sustained pressure. at the level of the cystic point, inviting the patient to take a deep inspiration; in this way, the liver and gallbladder move downward, causing the gallbladder to crash against the doctor's fingers. It will be positive if the patient experiences acute pain, which forces him to interrupt inspiration.

When leaks or small perforations occur in appendicitis, cholecystitis or diverticulitis, the mobile organs of the abdomen, greater omentum, loops of the small intestine and sigmoid colon, concur to block the inflammatory process to prevent its spread. The palpatory sensation of an organ covered by omentum and limb loops, plus the inflammatory component, is called plastron; compressing it can cause exquisite pain. Given findings of these characteristics, it should be considered that the process takes a certain time of evolution (eg, several days).

Percussion

This procedure is important as it can reveal:

- Pneumoperitoneum : due to perforation of the hollow viscus (gastroduodenal ulcer) with disappearance of liver dullness (Jobert's sign); the air gap must be sought. On the standing x-ray, an aerial crescent is seen between the diaphragm and the liver (Popper's sign).

- Rupture of the spleen : there is a discussion of the Traube airspace, which becomes less as it increases. perisplenic hematoma.

- Ascites : there are acute abdomen pictures that present with peritoneal effusion, such as peritoneal tuberculosis, carcinomatosis, etc.

- Intestinal occlusion : bloat is found, and areas of dullness can also be established when there is blocked or free intra-abdominal fluid. In the latter case, the patient should be changed to decubitus, observing if these areas are displaced.

Abdominal percussion should always be completed with chest percussion to rule out: the possibility of diaphragmatic pleurisy, lower lobe pneumonia, pericarditis, or pleural effusion. Any of the aforementioned conditions can be confused with intra-abdominal processes.

Auscultation

Peristaltic sounds. In the areas of partial obstruction, extraordinarily loud noises can be discovered, due to the energetic peristaltic action of the segment with hypertrophied musculature, which tries to expel its contents through the stenosed region. Peristaltic noises heard in intestinal obstruction are characteristic and high-pitched, producing a sound similar to that caused by the expression of a very small column of fluid into a hollow, resonant cavity. (syringe jet noise). Auscultation of the abdomen is important to differentiate intestinal obstruction from peritonitis. The presence of rumbling is against a diagnosis of peritonitis,

Vascular sounds. The presence of noises, buzzing, friction, an upper abdominal murmur, can give the initial clue to a mesenteric artery stenosis. A murmur over the aortic bifurcation may indicate obliteration of the terminal aorta. In fact, in hypertensive patients, an abdominal murmur is almost always due to an occlusive disease of the terminal aorta or the iliac vessels. Other abnormal noises can be heard in case of aneurysms, renal artery diseases, etc. A systolic epigastric murmur, accentuated by inspiration, has been described as a sign of a certain preangiographic diagnosis in celiac artery syndrome. Systolic murmurs are auscultated in the left upper quadrant associated with a tortuous splenic artery, hypersplenism, splenomegaly, and arteriovenous fistulas. and in the right upper quadrant related to the enlarged and tortuous hepatic arteries. of cirrhosis. Murmurs can also be heard below the right costal margin, over an enlarged liver, associated with severe anemia.

Friction rubs . If they are heard over the liver area, they suggest a carcinoma or perihepatitis.

Rectal examination and gynecological examination

A physical examination should not be completed without the digital rectal examination. This procedure is important in the presence of intestinal symptoms such as constipation, bleeding, diarrhea, pain in the lower abdomen, pelvic disease, manifestations of the urinary tract, and suspected malignancies. It is performed with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, with the thighs flexed, after inspection of the perianal skin to discover fistulas, hemorrhoids, abscesses, and scratching lesions due to itching. The maneuver should be slow and smooth, first observing the resistance obtained by the tone of the anal sphincter (spasticity, atony or normality). Exaggerated pain during introduction will reveal a hypersensitivity reaction, duct ulceration, hemorrhoids, fissure, fistula, abscess, cryptitis, or papillitis. In the later stages of ulcerative colitis, a marked stenosis of the rectum may be seen. Rectum carcinoma is usually easily identified by its irregularity and hardness, as well as because tumor invasion alters the walls of the rectum. The patient may be asked to make an effort with the abdominal muscles, defecatory type; In this way, neoplasms that would be out of the finger's reach in a routine examination can be palpated. Rectal examination also includes palpation of the prostate. in men and the cervix in women. If in a patient the inflamed appendix occupies a low place in the pelvis; There may be tenderness in the fundus of the peritoneal sac, located to the right of the rectosigmoid. In cases of sigmoid diverticular inflammatory mass, pain in the left cul-de-sac will be appreciated. Sometimes a sensation of swelling or filling will be noticed; Likewise, a granulomatous mass can be discovered, or an abscess due to a terminal regional ileitis. In pelvic peritonitis and pelvic abscess of any kind, the digital scan often triggers pain on the side of the lesion, and the pressure exerted on the rectum by an actual tumor can sometimes be felt. If carcinoma is suspected in any region of the abdomen, and especially in the stomach, careful palpation of the upper part of the anterior wall of the rectum, above the prostate. in the male and the cervix in the female, it may discover a carcinomatous infiltration of the pelvic floor, Between the bladder or uterus and the anterior wall of the rectum, a mass with this location is usually due to penetrative metastasis and is often called a Blumer's ridge. Sometimes the entire pelvis is invaded and a hard mass, called. "frozen pelvis". Most patients with gastric carcinoma die long before Blumer's ridge is discovered.

The bimanual vaginal examination is important in all patients; inspection of the cervix, as well as examination of genital and urethral discharge, should be part of the examination. Hypersensitivity to movement of the cervix indicates inflammation of the uterus and adnexa; a soft neck, bloody discharge, and palpation of an adnexal mass suggest pregnancy. ruptured extrauterine.

Study methodology

Laboratory

It should be noted that the laboratory is only complementary to the clinical examination, and that the diagnosis should in no way be based on these data, although the value of amylasemia and amylauria in acute pancreatitis must be emphasized.

Red blood cell count . An abnormally high red blood cell count may indicate that the patient is dehydrated. In the first. hours following major bleeding, count remains normal; newly: modified after 24 hours. A low hematocrit indicates a decrease in the number, and. red blood cell size and is seen in:

- Acute hemorrhages, intraperitoneal or in the lumen of the digestive tract.

- Chronic bleeding (reflux esophagitis, gastroduodenal ulcers, Duhring polymorphous dermatitis).

- Infections (sepsis).

- Chronic renal failure.

A high hematocrit indicates a decrease in plasma volume, or the formation of a third space at the retroperitoneal level (pancreatitis), in the lumen of the intestine (ileus) or in the abdominal cavity (peritonitis).

White blood cell count . White blood cells are increased (more than 10,000 / mm3):

- When there is necrosis of the viscera, for example, in mesenteric embolism, or in intestinal obstructions with strangulation and in acute pancreatitis.

- In inflammatory processes, such as acute cholecystitis, acute appendicitis, diverticulitis, etc.

Low or normal white blood cells are seen in viral infections, gastroenteritis, mesenteric adenitis, and typhoid fever.

When the inflammatory process progresses towards suppuration, the number of white blood cells increases, constituting an important sign to suspect abscess.

Before a patient with frank signs of peritonitis that he presents. leukopenia should not be underestimated the diagnosis of abdominal sepsis. A decrease in white blood cells in the peripheral blood is not uncommon when there is massive contamination of the peritoneum, due to the migration of leukocytes towards the inflammatory focus.

Sedimentation rate . It is accelerated in all inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic processes.

Urine . When the urine has a mahogany color, similar to strong tea, the presence of direct bilirubin is inferred. If its agitation produces a yellow, greenish foam, it indicates the presence of bile salts.

It is also helpful to know the density of your urine; if it is low in a patient who vomits, a urea dose should be requested. and creatinine because you may be facing kidney failure. High density is seen in dehydrated patients. If the urine is of a normal color) but exposed to the air it assumes a color similar to port wine, it could be the painful abdominal picture of a porphyria. The presence of glycosuria may indicate previously undetected diabetes. When faced with a urinary tract infection, pyocytes (pyuria) appear in the urine, which can also appear due to the proximity of an inflamed appendix to the ureter or bladder. In 70% of cases of retrocecal appendicitis, erythrocytes are observed in the urine.

Amylase and lipase in blood. Amylasemia and amylasuria are elevated when there is acute pancreatic damage, and on the other hand they remain normal in pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis; they also rise in acute outbreaks of the latter. In acute pancreatitis with great destruction of the pancreas, such as necrotic, hemorrhagic forms, or those that occur in type I, IV, or V hyperlipidemias, normal or low amylasemias are obtained. Extrapancreatic processes such as acute appendicitis, adnexitis, perforated ulcer, neo, intestinal messenteric infarction, ruptured extrauterine pregnancy, and extra-abdominal processes such as parotitis (urlian fever) can present with elevated amylasemia. They rarely exceed 300 Wohlgemuth units if the cause is extrapancreatic. It should be noted that if there is acute or chronic kidney failure, amylase will be eliminated by the kidney with more difficulty; In these circumstances, amylasemias can be found higher and for a longer time than in patients with preserved renal function.

Lipase increases in acute pancreatitis. Amylasemia generally returns to its normal value 48 hours after the onset of symptoms; on the contrary, lipase remains high up to 72 hours.

Transaminases . The elevation of these enzymes in patients with subcostal pain and jaundice will confirm the condition of liver inflammation.

Hypercalcemia . It can be seen in patients with hyperparathyroid crisis.

Alkaline phosphatase . In general, its increase indicates bone disease, osteoblastic processes, liver disease, cholestasis. intra or extrahepatic, or liver occupying mass. The highest values are found in the hepatoma.

Diagnostic abdominal puncture

It can be performed in any area of the abdomen, although it is preferred to be in the area close to acute abdominal pain in the event that the process is localized; if it is diffuse, it will be done at the left Mc Burney point.

With a thick intramuscular needle adapted to a syringe with a local anesthetic (lidocaine), the abdominal wall is infiltrated and the needle is then inserted perpendicular to the wall. until you have the sensation of going through. the peritoneum. A vacuum is made with the plunger and the liquid is obtained; It can happen that no fluid is collected and this can happen because the needle is not in the peritoneum or because there is no fluid. Before giving the negative puncture, air should be injected and then aspirated; if more air is collected than injected, it may be in an intestinal loop.

If an "unsatisfactory" (painful) Douglas sac is found on palpation, it may be punctured; it is useful in case of effusions and abscesses or a ruptured extrauterine pregnancy.

The macroscopic examination of the abdominal contents obtained by puncture may yield the following data:

- Pus : liquid with a creamy appearance, choppy: do, sometimes bloody. It is seen in purulent peritonitis. perforated pyocolecyst, ruptured and infected hydatid cyst, ruptured liver or subphrenic abscess, and so on.

- Bile : yellowish gold color. The choleperitoneum is generally iatrogenic.

- Bilious fluid : greenish color, sometimes with purulent clumps. It is associated with acute perforated cholecystitis, filtering biliary cholecystitis (gallbladder dew).

- Bloody fluid : like blood-washing water: in acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis.

- Blood : in ruptured extrauterine pregnancy, liver or spleen trauma, peritoneal carcinomatosis, ruptured ovarian follicle.

- Citrine fluid : in tuberculous peritonitis, localized inflammatory processes (few milliliters), acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, Diverticulitis, etc.

- Crystalline fluid (like rock crystal): peritoneal hydatidosis, ovarian cyst, embryonic remains (Wolffian duct).

- Mucous fluid : with whitish or bloody lumps and acidic pH. It corresponds to gastric juice from perforation of an ulcer. gastroduodenal.

- Brownish fluid : choppy and smelling of fecal matter, due to intestinal perforation (diverticulitis, ulcerative colitis, etc.). It may also be that the intestine has been punctured.

- Urine : yellowish mahogany color, due to puncture of the distended bladder, or due to injury and perforation of the urinary tract.

- Chylous fluid : milky appearance, due to obstruction of the thoracic duct; in lymphomas, liver cirrhosis, dyslipidemias, etc.

Radiology

The various processes that make up the acute abdomen have a radiological expression, sometimes so characteristic that it could be called pathognomonic.

Radioscopy . It is the first method to be carried out, in a standing position, if the general condition. the sick person allows it.

First, the thorax will be seen, where the possible existence of an acute pleuropulmonary process (atelectasis, pneumonia, pleuritis, etc.), of thoracoabdominal trauma complicated with hemothorax or pneumothorax, which may be concealed by an apparently more striking abdominal symptomatology, will be investigated , or they can simulate an abdominal picture. The pleural cul-de-sac should be examined in search of a possible pleural effusion, even minimal "as occurs in acute pancreatitis, in which it is located in the left pleural cul-de-sac. The mobility of the two hemidiaphragms will rule out the fixation of one of the them, as can be seen in subphrenic abscesses, in parietocolic collections, in perforated ulcers, in acute peritonitis, etc. On occasions, air is observed in the subdiaphragmatic space,

Radiograph . The standing position facilitates the clear observation of the gas-liquid contrast areas, due to the accumulation of both elements in the distended intestinal loop; This position also prevails to establish the possible existence of liquid spills in the peritoneal cavity, or gas (pneumoperitoneum), which will be sought with a predilection in the subphrenic space The position in supine position It allows to clarify elements of fine detail, such as the Contact areas of the intestinal loops: also in the reflection areas of the peritoneum, erased skin is valuable to indicate the presence of a neighboring inflammatory or hematic collection.

The radiological examination of the acute abdomen by means of a barium enema allows us to distinguish; before an obstructive condition, if it is located in the colon or small intestine. Delivering barium by mouth has a very relative value since its arrival at the point of obstruction is dependent on the height of the latter and can even be an aggravating factor of the obstruction, due to impaction of the radiopaque suspension. Barium can escape through the interruption of gastroduodenal perforations, causing peritoneal abnormalities. A safer method is to instill a small amount of barium through a duodenal tube, lodged in the stomach, under fluoroscopic control (exceptional method).

Radiological elements visible on examination of an acute abdomen

Abdominal distension. It is the fundamental pathophysiological component of ileus. It is established by the progressive accumulation of gas and liquid in the intestinal lumen by blocking its transit, with increasing dilation of the intestine.

The liquid has a radiological opacity greater than that of air. In dorsal decubitus, and even better in the standing position, images in levels can be observed, given by the separation between the liquid in the lower part and the air in the upper part, observable in the cases of ileus and intestinal obstruction (Fig. 31 -two).

There are sectors of the digestive tract, such as the stomach; the first portion of the duodenum and colon, in which some accumulation of gas is normally seen. In other sectors, this finding must be considered. pathological. Free cavity gas, or pneumoperitoneum, is evidenced by placing the individual in a standing position, so that the air is lodged in the highest portion. of the abdomen: the subphrenic spaces., The air may be disposed between the liver, and

In an obese patient, excess subdiaphragmatic fat can occasionally be seen as a bilateral radiolucent image that, unlike the pneumoperitoneum, does not shift forward when a supine abdominal radiograph with the lateral ray is obtained.

Free cavity fluid (hemoperitoneum, choleperitoneum) is difficult to demonstrate: radiologically when not in contact with gas, except in very important effusions, which give an opacity in the pelvis. Fat has an X-ray density intermediate between air and water; Faced with an inflammatory, peritoneal or juxtaperitoneal process, the edema must also compromise the fat, which, when infiltrated with water, will acquire a higher radiological density; The so-called clear lines of peritoneal fat will then be erased and a useful sign for the diagnosis of inflammatory involvement will be constituted: peritoneal, appendicular, Douglas, peritoneal abscess, etc. A sign that characterizes the presence of especially fibrinous peritoneal exudate is the increased thickness of the lines of contact between the intestinal loops; the angles formed between them become curvilinear and configure what has been called the “sign of the plaster”. The thickness of the contact areas is conditioned by two fundamental elements: a) the intestinal walls themselves, b) the substances that can interpose between said walls in contact. Sometimes plaster images may appear corresponding to intraparietal edema of the distended intestine in certain cases of ileus.

Remembering the normal distribution of the hollow viscera in the abdomen, it is possible, if a distended loop is observed, to make a presumptive diagnosis of its location. If the flanks are free or occupied, the distention will be suspected to involve the small intestine in the first case and the large intestine in the second.

Remembering the normal distribution of the hollow viscera in the abdomen, it is possible, if a distended loop is observed, to make a presumptive diagnosis of its location. If the flanks are free or occupied, the distention will be suspected to involve the small intestine in the first case and the large intestine in the second.

In duodenojejunal angle distention, this and its immediate loops lodge in the left hypochondrium and reach the midline as the obstruction is lower; that is, they follow the arrangement of the mesentery.

The ileum, in its final part, occupies the right flank, descending to the right iliac fossa in its most juxtacecal portion.

When the obstruction is high, that is, jejunal, thin grooves can be observed that leave small spaces between them, corresponding to the Kerkring folds of the intestinal mucosa, originating in the conniving valves. Is. arrangement corresponds to the so-called "pile of coins" aspect; This is clearly seen in mechanical occlusions, and they result from the exaggerated peristalsis of the loop to overcome the obstacle; At the ileum level, it will be seen that the folds have disappeared, the contour of the intestinal loop being distended and smooth.

In the large intestine, both the classic dents caused by the contraction of the bands; Longitudinal bundles, such as the grooves corresponding to the semilunar folds of the mucosa, can be "erased" under certain circumstances.

Acute peritonitis. It is noted:

- Peritoneal fibrinous exudate: plaster sign.

- Effacement of the contours of the psoas, kidney, spleen, and liver due to increased fibrinous exudate and free fluid in the peritoneal cavity

Acute pancreatitis. The following signs can be observed:

- Left pleural effusion.

- Elevation of the left hemidiaphragm (paresis).

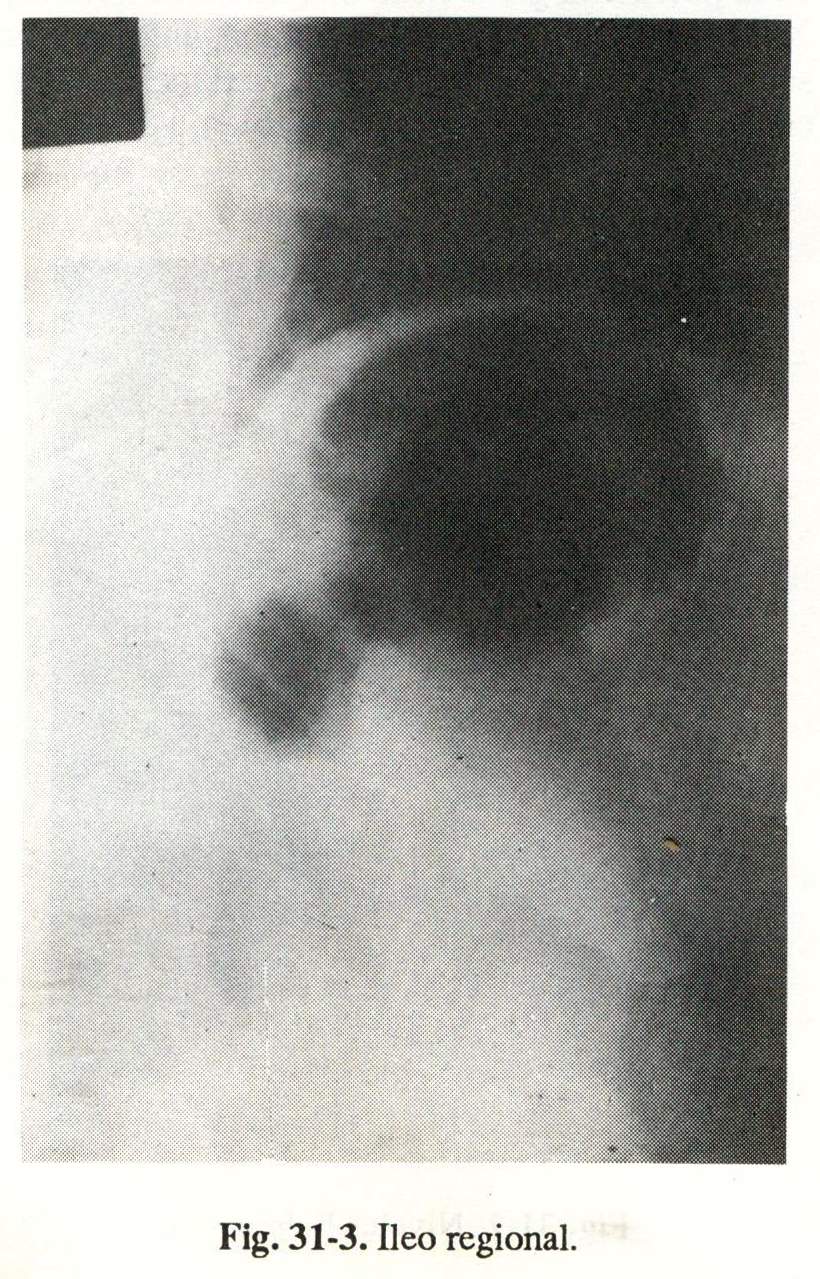

- Partial or regional ileum (fig. 31-3).

- Stomach displaced up.

- Transverse colon very distended.

- Gobiet's sign (severe distention of the epigastrium).

- Duodenal arch opening (barium contrast).

- Opacity of the left lung base.

- Opacity of the pancreatic region.

- Distension of the jejunal loops.

- Free cavity spill.

Hollow viscera perforation. Standing patient:

- Gas in the right subdiaphragmatic space in the gastroduodenal perforations (crescent sign).

- Gas in the left subdiaphragmatic space in sigmoid and diverticulum perforations.

Patient in supine position:

- Kudleck's prehepatic pneumoperitoneum.

- Gas escapes do not always occur in perforations, since the perforation may have closed, blocked quickly, or the viscera may not contain an insufficient amount of air.

Trauma to the liver or spleen. The following radiological signs may be observed:

- Raised hemidiaphragm.

- Diffuse opacity due to hemoperitoneum.

- Ileocolonic meteorism.

- Gastric chamber and colon displaced.

-

Lumbar aortic angiography, by femoral catheterization, will show:

- extravasation of radiopaque substance

- displacement of major organs or arteries

- altered visceral contour

- occlusion of arterial branches

- false aneurysms

- early venous filling

Trauma to the posterior aspect of the duodenum. They can be observed:

- Gas bubbles in retroperitoneum.

- Clear outer border of the psoas and right kidney outline.

Strangulating occlusion (volvulus, postoperative flanges, neoplastic stenosis):

- Increased handle size.

- Smooth edges.

- Round shape.

- Image in a semicircle.

Mechanical occlusion of the small intestine. The following signs may appear:

- Air-fluid levels (standing radiography).

- Distension of the viscus above the occlusion.

- At the level of the jejunum, image in a pile of coins (horizontal decubitus radiography).

- Disappearance of gases in the colon.

The presence of gases in the digestive tract, whether they are the product of swallowed air (70%), of putrefaction or intestinal fermentation, or of vascular gas exchange, is not visible radiologically under physiological conditions, except at the level of the stomach or colon , where the digestive content is temporarily detained. In certain pathological processes, the presence of gases makes it possible to identify the liquids that remain below, and when the rays are parallel to the surfaces of both chambers, the so-called air-fluid levels are drawn. The absence of gaseous images. in the large intestine, it constitutes an element of radiological diagnostic value in mechanical occlusion of the thin.

On some occasions, the ingestion of opaque substance has been used to diagnose the location and probable nature of the obstacle; Thus, it has been possible to obtain, for example, the clear images provided by gallstone ileus (snake, with a clear head) that is difficult to perform: because the patient generally presents. severe vomiting, and it takes a long time for the opaque substance to reach the site of the stenosis.

Mechanical obstruction of the colon (usually neoplastic):

- With continent ileocecal valve: enormous distention of the proximal colon with respect to the obstacle with risk of cecal rupture (Fig. 31-4). Liquid levels, wide, few in number, located at the level of the flanks, corresponding to the ascending and descending colon, and in the central part and the pelvis those of the transverse and sigmoid. The presence of widely spaced semilunar folds is noted, which do not cross the entire lumen of the loop, unlike the connivents of the thin one that go from wall to wall (horizontal decubitus radiography).

- With incontinent ileocecal valve: distended colonic loop, mechanical distention of the ileum, and presence of jejunoileal levels.

- Volvulus of megacolicosigma: a huge loop that extends from the pelvis to the hypochondrium, with smooth edges and no folds (Fig. 31-5).

- Faecal clumps in the sigmoid loop or rectum: opaque images with an inhomogeneous appearance (sponge images) (Fig. 31-6).

Miscellaneous direct abdominal radiology

Miscellaneous direct abdominal radiology

Radiopaque densities. Radiopaque images of different significance can be seen in relation to the clinical picture:

- Calcifications: may correspond to phleboliths, mesenteric ganglia, chronic calcifying pancreatitis, fibromas; blood vessels in the elderly, edge of an aortic aneurysm. teeth in a pelvic mass, which are pathognomonic for a dermoid cyst of the ovary.

- Foreign bodies: dentures, coins, etc.

- Soft tissue masses: distended bladder, enlarged uterus, pancreatic pseudocyst, abscess.

In the right upper quadrant, radiopaque images require a differential diagnosis between gallbladder and kidney stones; but a radiograph of peñl1 will show that the projection of the opacity is anterior in the first case and posterior in the second.

In the right iliac fossa, the visualization of calcium images may correspond to appendicoliths.

In the right iliac fossa, the visualization of calcium images may correspond to appendicoliths.

The disappearance of the shadow of. psoas muscles: it is observed when there is retroperitoneal pathology: blood, plasma, pus, as in acute pancreatitis, retroperitoneal hematomas, perinephritic suppurations.

Abdominal CT scan

Abdominal CT scan

The application. Echotomography in the study of hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases meant a remarkable diagnostic advance, also used in cases of acute abdomen especially because of the innocuous and rapid procedure.

Liver . Diffuse lesions: cirrhosis, fatty infiltration, sarcoidosis, liver fibrosis, Hodgkin's disease, granulomatosis. Focal lesions: hydatid cyst, congenital cysts, primitive or metastatic tumors, abscesses.

Bile ducts . Gallstones, gallstones; cholecystitis (difficult), choledochal lithiasis, intra- and extrahepatic cholestasis.

Pancreas . Acute and chronic pancreatitis, pseudocysts of the pancreas .; pancreatic abscess, tumors of the pancreas.

Spleen : Splenomegaly, trauma.

Abdominal lymphadenopathy . Para-aortic, retroperitoneal, hilar of organs, Hodlgkin's disease, lymphosarcomas.

Other processes . Ascites, ovarian cysts, vascular disorders (dilations, compressions, thrombosis, aneurysms).

Computed tomography

Computed tomography, or computed axial tomography, is a very advanced imaging method that contributes to the diagnosis in certain cases of acute abdomen. Its indications are:

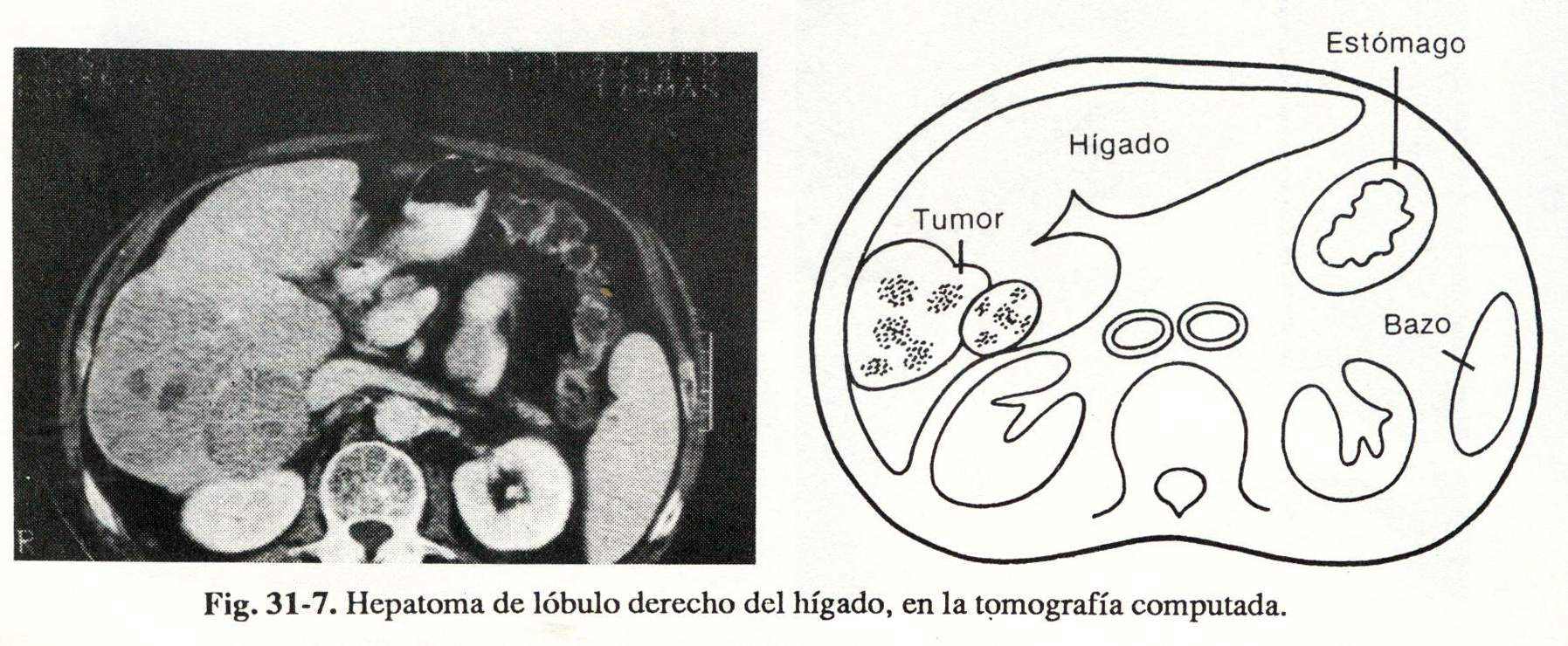

Liver . Localized lesions: tumors, cysts, abscesses, hematomas (Fig. 31-7). Fat degeneration, hemochromatosis, cirrhosis. Bile duct dilation and differential diagnosis of jaundice. Location of lesions for percutaneous biopsy. Ascites

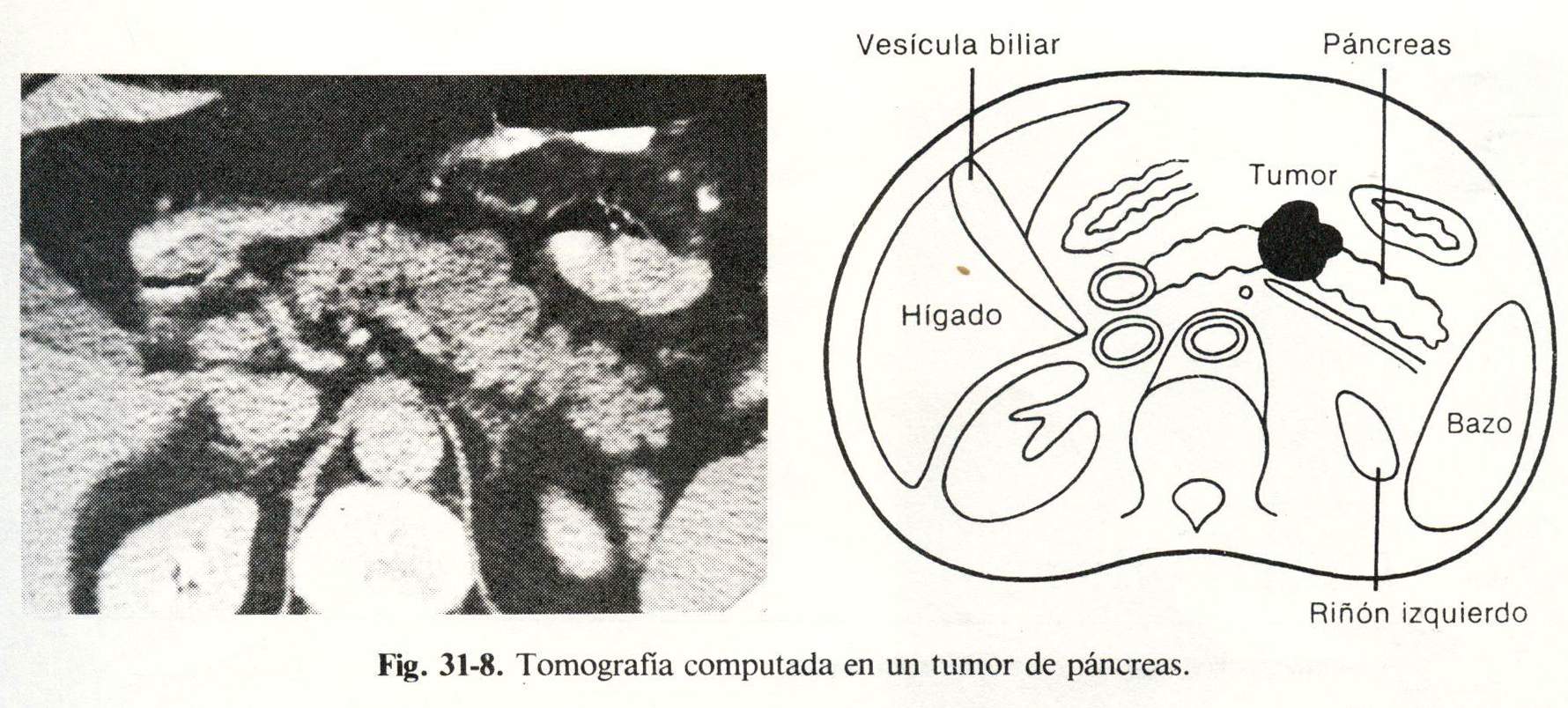

Pancreas . Acute pancreatitis. Cystic abnormalities: pseudocysts, abscesses, hematomas; cystadenomas; carcinomas .: cystic. Calcifications Atrophy. Wirsung duct dilation. Neoplasms and benign tumors (Fig. 31-8).